Today's greatest companies have created

Radically New Rules

Firms of endearment is a book about these new rules that are transforming businesses from the inside out

Today's greatest companies are fueled by passion and purpose, not cash. They earn large profits by helping all thier stakeholders thrive: customers, investors, employees, partners, communities, and society. These rare, authentic firms of endearment act in powerfully positive ways that stakeholders recognize, value, admire, and even love. They make the world better by the way they do business-and the world responds.

They had created radically new rules. This extensively updated book will help you master those new rules, learn from their newest experiences, build your great firm of endearment, change the world, and succeed on every level that matters.

Check out the new rules

Build a high-performance business on love (It can be done. We'll prove it.)

Help people find the self-actualization they're so desperately seeking

Join capitalism's radical social transformation—or fall by the wayside

Don't just talk about creating a happy, productive workplace: DO IT!

Honor the unspoken emotional contract you share with your stakeholders

Create partner relationships that really are mutually beneficial

Build a company that communities welcome enthusiastically

Help all your stakeholders win, including your investors

Meet the

Authors

Raj Sisodia is the F.W. Olin Distinguished Professor of Global Business and Whole Foods Market Research Scholar in Conscious Capitalism at Babson College in Wellesley, MA. He is also co-founder and co-chairman of Conscious Capitalism, Inc. He has a Ph.D. in marketing from Columbia University. Raj is the co-author of The New York Times bestseller Conscious Capitalism: Liberating the Heroic Spirit of Business (Harvard Business Review Publishing, 2013). In 2003, he was cited as one of "50 Leading Marketing Thinkers” by the Chartered Institute of Marketing. He was named one of "Ten Outstanding Trailblazers of 2010” by Good Business International, and one of the "Top 100 Thought Leaders in Trustworthy Business Behavior” by Trust Across America for 2010 and 2011. Raj has published seven books and more than 100 academic articles. He has consulted with and taught executive programs for numerous companies, including AT&T, Nokia, LG, DPDHL, POSCO, Kraft Foods, Whole Foods Market, Tata, Siemens, Sprint, Volvo, IBM, Walmart, Rabobank, McDonalds, and Southern California Edison. He is on the Board of Directors of The Container Store and Mastek, Ltd., and is a trustee of Conscious Capitalism, Inc. For more details, see www.rajsisodia.com

Jag Sheth is the Charles H. Kellstadt Professor of Marketing in the Gouizeta Business School at Emory University. He has published 26 books, more than 400 articles, and is nationally and internationally known for his scholarly contributions in consumer behavior, relationship marketing, competitive strategy, and geopolitical analysis. His book The Rule of Three (Free Press, 2002), coauthored with Raj Sisodia, has altered current notions on competition in business. This book has been translated into five languages and was the subject of a seven-part television series by CNBC Asia. Jag’s list of consulting clients around the world is long and impressive, including AT&T, GE, Motorola, Whirlpool, and 3M, to name just a few. He is frequently quoted and interviewed by The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Fortune, Financial Times, and radio shows and television networks such as CNN, Lou Dobbs, and more. He is also on the Board of Directors of several public companies. In 2004, he was honored with the two highest awards bestowed by the American Marketing Association: the Richard D. Irwin Distinguished Marketing Educator Award and the Charles Coolidge Parlin Award. For more details, see www.jagsheth.com

David B. Wolfe The late David B. Wolfe was an internationally recognized customer behavior expert in middle-age and older markets. He was the author of Serving the Ageless Market (McGraw-Hill, 1990) and Ageless Marketing: Strategies for Connecting with the Hearts and Minds of the New Customer Majority (Dearborn Publishing, 2003). David’s consulting assignments took him to Asia, Africa, Europe, and throughout North America. He was widely published in publications in the U.S. and abroad. He also consulted to numerous Fortune 100 companies, including American Express, AT&T, Coca-Cola, General Motors, Hartford Insurance, Marriott, MetLife, Prudential Securities, and Textron.

Praise for

The Book

Check out what management

experts have to say about the book

Browse

Inside the book

Prologue - A Whole New World

The future is disorder. A door like this has opened up only five or six times since we got up on our hind legs. It’s the best possible time to be alive, when almost everything you thought you knew is wrong.

The mathematician Valentine,

in Tom Stoppard’s play Arcadia

This book reaches the public eye at the dawn of a new era in human history—perhaps more so than any previous era that inspired historians to give it a name signifying its import. Looking back hundreds of years—thousands of years, say some1—this new era may be unmatched in the scale of its effect on humankind. Numerous credible authors have testified in their writings that something this big is happening. Francis Fukuyama declared the end of a major cultural era in his famous and controversial essay "The End of History” (1989). A little later, Science magazine editor David Lindley foretold the demise of the Holy Grail of physics—the General Unified Theory—in The End of Physics (1993).

The next year, British economist David Simpson claimed that macroeconomics had outlived its usefulness in The End of Macro-Economics (1994). Then, science writer John Horgan ticked off legions of scientists with his provocative book The End of Science (1997). That same year, Nobel Laureate chemist Ilya Prigogine told us in The End of Uncertainty (1997) of an imminent broad-reaching shift in scientific worldview that would make much of what stands as scientific truth today scientific myth tomorrow.

So many endings must mean so many new beginnings. Around the start of the 1990s, virtually no major field of human endeavor was spared from predictions of its ending—not literally, but certainly in terms of past conceptualizations of its nature. The world of business is no exception. It is experiencing far-reaching changes in our understanding of its fundamental purposes and how companies should operate. Indeed, looking at the magnitude of change in the business world, it is not overreaching to suggest that an historic social transformation of capitalism is underway.

Twenty or so years ago, just as the Internet was going mainstream, few could have credibly predicted the scale of this transformation. In this book, we provide some measure of that scale by profiling companies that have broadened their purpose beyond the creation of shareholder wealth to act as agents for the larger good. We view these companies not as outliers but as the vanguard of a new business mainstream.

We call this era of epochal change the "Age of Transcendence.” The dictionary defines transcendence as a "state of excelling or surpassing or going beyond usual limits.”2 We’re not the first to speak of a transcendent shift in the zeitgeist of contemporary society; Columbia University humanities professor Andrew Delbanco says, "The most striking feature of contemporary culture is the unslaked craving for transcendence.”3 This craving for transcendence could be playing a strong role in the erosion of the dominance of scientifically grounded certainty, which has characterized worldviews in western societies since the dawn of modern science. Subjective perspectives based on how people feel have gained greater acceptance in recent times.

Others have taken note of the rising subjectivity of worldviews. One is French philosopher Pierre Levy, who has devoted his professional life to studying the cultural and cognitive impacts of digital technologies. He believes that the shift toward subjectivity may prove to be one of the most important considerations in business in this century.4 Levy also believes that Ayn Rand–style objectivism, firmly embraced by Milton Friedman and his proteges, is passing into history as feelings and intuition have risen in stature in the common mind. Malcolm Gladwell’s bestselling book on intuition, Blink, is a testament to that, as is James Surowiecki’s The Wisdom of Crowds.

The dramatic upsurge of interest in spirituality in the U.S. that has helped spawn stadium-sized "mega churches” is another indication that something big is happening in the bedrock of culture. Numerous consumer surveys report that people are looking less to "things” and more to experiences to achieve satisfaction with their lives.5 For many, the experiences they most covet transcend a world that is materialistically defined by science, and for that matter most of traditional business enterprise.

People who lead companies are not insulated from the influences of culture. After all, they drink from the same cultural waters as the customers they serve and the employees they lead. The executives we write about as exemplars in this book reflect in their managerial philosophies the changes in culture we’ve been talking about. They are champions of a new, humanistic vision of capitalism’s role in society. It is a vision that transcends the narrower perspectives of most companies in the past, rising to embrace the common welfare in its concerns. Former Timberland CEO Jeffrey Swartz (whose company has been acquired by VF Corp.) unabashedly said that his company’s primary mission was "Make the world a better place.” But Swartz and the other executives we hold up as role models in this book are not starry-eyed do-gooders. They are resolute and highly successful business professionals who augment their human-centered company vision with sound management skills and an unswerving commitment to do good by all who are touched by their companies.

We call their companies "firms of endearment” because they strive through their words and deeds to endear themselves to all their primary stakeholders—customers, employees, suppliers, communities, and shareholders—by aligning the interests of all in such a way that no stakeholder group gains at the expense of other stakeholder groups; rather, they all prosper together. These executives are driven as much by what they believe to be right (subjectively grounded morality) as by what others might more objectively claim to be right.

Ponder for a moment what the results of a Conference Board survey say about the moral outlook in executive suites across the country. Seven hundred executives were asked why their companies engaged in social or citizenship initiatives. Only 12 percent mentioned business strategy. Three percent mentioned customer attraction and retention, and one percent cited public expectations.

The remaining 84 percent said they were driven by motivations such as improving society, company traditions, and their personal values.6 We don’t think members of this 84 percent all sat down and calculated in rational fashion the direct payoff of carrying out their duties according to high moral standards. More likely, we believe, most simply feel in their gut what they should be doing. This is how movements and revolutions unfold: as much from the heart as from the mind. What we write about in this book is a powerful movement if not altogether a revolution.

We are poised precariously at what physicists call a bifurcation point—an interregnum of normalcy between the poles of death and birth (or rebirth), when an old order faces its end and a new order struggles to emerge from its fetal state. At such times, the future becomes more uncertain than usual because events within the time and space boundaries of a bifurcation point have infinite possible outcomes. This is why Valentine declared, "The future is disorder” but challenges us to join efforts to bring forth a new order with the yeasty lure: "It’s the best possible time to be alive when almost everything you thought you knew is wrong.”

Humankind is entering a realm where no one has gone before. Its landscape is as unfamiliar to us as the world that we’ve known until now would be to a time traveler from the eighteenth century. Let’s travel back in time to better appreciate the evolutionary nature of culture through brief reflections on the antecedent two cultural ages in U.S. history from which the Age of Transcendence is emerging.

The Age of Empowerment

We call the first cultural era in America the "Age of Empowerment.” The signing of the Declaration of Independence and publication of Adam Smith’s An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations in 1776 marked its beginning. That these two epochal events in human history occurred in the same year is an extraordinary historic coincidence. The former event was about a free society, the latter about free markets. Joined at the hip, democracy and capitalism marched into the future to bring forth a whole new world, one that would elevate the lot of the common man to heights never experienced or imagined before in human history.

For the first time in history, ordinary people were empowered by codified law to shape their own destinies. People born without social distinction could raise themselves from abject poverty to the highest public and private offices. A free market economy aided their efforts. Liberal education and laws that rewarded industry supported America’s determination to become a great nation. As decades went on, millions of families rose out of subsistence existence. The aristocratic culture of Europe may have generated great philosophic thinking in the Age of Enlightenment, but common folk in America generated great material accomplishment in the Age of Empowerment. By the end of the Age of Empowerment, which we mark around 1880, America was connected coast-to-coast by telegraph lines, railroads, a single currency, and a national banking system that the Lincoln presidency had established. Another great accomplishment of the Lincoln administration was the establishment of the land grant college program that increasingly brought the benefits of higher education to the masses. The nation was primed for its next great cultural era.

The Age of Knowledge

The intellectual and economic liberation of the masses paved the way for the Age of Knowledge. Within a half-dozen years of 1880, Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone, and Thomas Edison invented the phonograph, the first practical incandescent light bulb, and the first central electrical power system.

During the Age of Knowledge, the U.S. transitioned rapidly from an agrarian to an industrial society. Science exploded into daily life. The time from laboratory prototype to the marketplace came to be often measured in months instead of decades. Great scientific breakthroughs spawned great industries. And great industries created the modern consumer economy. Economic gains across society raised living standards to previously unimaginable heights. Childbirth and childhood deaths became rarities. Life expectancy in the U.S. shot up from 47 years at birth in 1900 to 76 years at birth by 1990.

Business management took a seeming leap forward in the early years of the twentieth century when Frederick Winslow Taylor introduced scientific discipline to the practice of management in Scientific Management (1911). Alfred P. Sloan invented the modern corporation after becoming president of General Motors in 1923. In 1921 John Watson, head of Johns Hopkins’ psychology department and founder of the behaviorist school of psychology, joined the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency to establish the first consumer research center in the nation. Science now undergirded the full spectrum of business—from product design and organizational management, to consumer research and marketing.

Ever since Ransom E. Olds established the first assembly line (no, it wasn’t Henry Ford; he just mechanized Olds’ assembly line), the operating focus of business has been on constant improvements in productivity—getting more and more from less and less. For a long time, this served society well. Quality of life steadily rose while the cost of living steadily fell. The material wellbeing of ordinary people reached astonishing levels. Materialism became the bedrock of business, society, and culture.

In time, however, preoccupation with productivity and cost cutting to improve bottom lines began to take a toll on communities, workers, their families, and the environment. Scores of communities fell into economic disrepair as companies abandoned them for venues promising lower operating costs. Legions of families endured abject suffering as their breadwinners struggled to find new jobs. Life was sucked out of villages, towns, and center cities across the nation. Sprawling slums filled with the carcasses of abandoned factories became unwelcoming neighborhoods. Apologists justified business decisions that wreaked havoc on individuals and their families and neighborhoods by invoking the Darwinian "survival of the fittest” theme. The pro-business argument was simple: To reap the benefits of capitalism, society must tolerate the pain it sometimes causes people on the lower rungs of society.

But growing numbers are now wondering, "How much more pain do we have to live with?” Ordinary citizens increasingly view commerce as lacking a human heart. They feel that most companies see them as just numbers to be controlled, manipulated, and exploited.

They know that to many companies they have little flesh-and-blood realness—that they have the same abstract quality as people on the ground have for pilots dropping bombs from 40,000 feet. But the times they are a-changing, as Bob Dylan sang in the 1960s.

New Republic senior editor Gregg Easterbrook has observed,

"A transition from material want to meaning want is in progress on an historically unprecedented scale—involving hundreds of millions of people—and may eventually be recognized as the principle cultural development of our age."

Welcome to the Age of Transcendence, the highest pinnacle that humanity has yet ascended to.

The Age of Transcendence

The point of tracing America’s cultural evolution since its founding is to focus attention on the idea that free societies continuously progress through processes of cultural evolution, the equivalent of a person’s evolutionary progress in what psychologists call “personality development.” Societies, like people, are driven to strive for being more today than they were yesterday, and more tomorrow than they are today. Indeed, Steve McIntosh suggests that this is the very purpose of evolution:

The evolutionary story of our origins has tremendous cultural power that transcends the boundaries of science; it shapes the view of who we are and why we are here. Yet many of the scientific luminaries responsible for educating the public about evolution tell us that it is an essentially random or accidental process with no larger meaning. However, as the scientific facts of evolution have increasingly come to light, these very facts demonstrate that the process of evolution is unmistakably progressive.

As we come to see how evolution progresses, this reveals evolution’s purpose—to grow toward ever-widening realizations of beauty, truth, and goodness.

While scientific discovery and technological development have been the primary catalysts in the evolution of culture, recent demographic changes have played quite a large role in reshaping culture. Aging populations are altering the course of humankind. But this is not the first time demography has reset the directions of humankind.

Recent findings by anthropologists indicate a sudden increase in longevity 30,000 years ago that changed human culture dramatically. The longevity gains created a population explosion among grandparents. For the first time in human history, relatively large numbers of postmenopausal women were available to support their daughters and granddaughters and to begin refining domestic life. More grandfathers were available to instruct young males in “the old ways,” thus strengthening generational continuity.

Many anthropologists regard the “grandparent phenomenon” as a major turning point in the cultural evolution of humankind. Among other benefits, the sharp increase in the grandparent population led to a moderation of the aggressive behavior of youth. This reduced tribal warfare, freeing tribal attention and energy to move toward higher states of cultural development.

Something similar could be happening today—that is, the rapid growth of an aging population is altering the zeitgeist of society, driving humankind toward higher states of cultural development. We can cite 1989 as the formal start of this new course because starting that year, most adults in the U.S. were 40 or older for the first time in history (the median age of adults now exceeds 45 across the American population and is more than 50 for Caucasians). Like an echo of the moderating influences brought about by an explosion in the grandparent population 30,000 years ago, the aging of the population in the vast majority of nations in the world today raises the prospects for a “kinder and gentler society”—to use Peggy Noonan’s words in a campaign speech she wrote for George H. W. Bush in 1988.

But another development occurring around the time the new “mature adult” majority came into being has also played a major role in catalyzing quantum changes in the bedrock of culture. Also in 1989, British software engineer Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web. Within a few short years, the Internet went from being an arcane communications tool used mostly by an elite few to a mainstream artifact used by tens of millions. The World Wide Web shifted the balance of information power to the masses. It dramatically changed how people interact with each other, democratized information flow, and forced companies to operate with far greater transparency. The Age of Transcendence bears similarities to what author Daniel Pink calls the “Conceptual Age” in his book A Whole New Mind. Pink defines the Conceptual Age as an “economy and a society built on the inventive, empathetic, big-picture capabilities of what’s rising.

He describes the Conceptual Age as the successor to the Information Age. We define our term for the same era a bit differently. The Age of Transcendence signifies a cultural watershed in which the physical (materialistic) influences that dominated culture in the twentieth century ebb while metaphysical (experiential) influences become stronger. This is helping to drive a shift in the foundations of culture from an objective base to a subjective base: people are increasingly relying on their own counsel to decide their course of action. This trait is typically present among people in midlife and older who are generally less subject to the “herd” behavior that is so prevalent among youth. That shift acknowledges a long suppressed idea in a world largely guided by the Newtonian certainty that Ilya Prigogine says is scattering to the winds: Ultimately, everything is personal.

Pink wrote enthusiastically about society moving from the more rational perspectives commonly associated with the left brain to the more emotional, intuitive perspectives usually associated with the right brain. He argued that companies in the U.S. need to move more toward right brain values to work an advantage over companies abroad who want to build relationships with American consumers. As he sees it, this means that U.S. companies must connect with what he calls the six senses of the Conceptual Age in product design, marketing, and customer relations. These six senses are design, story, symphony, empathy, play, and meaning. They all have deep roots in the brain’s right hemisphere.

However, the issue of change in the foundations of culture is not as simple as a matter of left brain versus right brain. We see the marketplace generally favoring companies that integrate both right and left brain perspectives to yield what Austrian neurologist Wolf Singer calls “unitive thinking,” which is a distinct third kind of thinking in Singer’s mind that he claims is the ultimate source of creativity.

In the wake of Rene Descartes’ formulation of the scientific method, the Western mind came to be dominated by “either/or” constructs that are largely moderated in the analytical left brain. That side of the brain tends to rank things hierarchically in categories. It routinely excludes from serious consideration what doesn’t fall into a clearly defined category. To put this in a business context, in exclusionary left brain thinking, stakeholders are relegated to categories. Connections between stakeholders in differing categories are incidental and accidental. The picture is quite different among firms of endearment (FoEs). Their leaders think in unitive fashion, approaching their tasks with holistic vision in which all players in the game of commerce are interconnected and significant.

Welcome, again, to the Age of Transcendence. Settle down, get comfortable, and read on. There are many new rules to learn, because almost everything you thought you knew could be wrong. We are going to be in this age for quite a while—probably for the rest of your life, and longer.

Foreword to the First Edition

Television producer and writer Norman Lear once told me, “When I’ve been most effective, I’ve listened to my inner voice.” Lear’s inner voice gave him the courage to transform television’s voice with his society-mocking domestic comedy All in the Family. Despite a string of impressive television successes, the raw texture of All in the Family made it a tough sell. But Lear was driven by a sense of mission on behalf of the entire country. His persistence paid off when CBS finally agreed to run the show.

Confident that one person can bring about big changes, Lear forced us to examine some of the most fetid prejudices that bubbled below the surface of society in the early 1970s. When All in the Family debuted, teeming throngs demanding civil rights for all and an end to the war in Vietnam swarmed in the nation’s streets and on its college campuses.

America’s easy-going post[nd]World War II composure was dissolving. Lear thought it was time that we tuned into our inner voices to hear what they had to say about how well we honored our claim to be a just society.

Firms of Endearment brings to mind Lear’s respect for the counsel of his inner voice. Judging by recent headlines, corporate America has too few leaders who open their mental ears to their inner voices. Rather, they take cues for their behavior from the external world where pursuit of power over others is the daily priority. Sadly, such ambitions weigh on us with a pervasive presence that extends far beyond the world of business. We are regularly served up headlines calling attention to abuses of power in government, academe, clinical research centers, social service agencies, and religious organizations. We seem overrun these days with people in high positions who compromise their organizations and the general welfare with their propensities for self-aggrandizement, avarice, and other perversions of public and private trust.

Happily, Firms of Endearment gives us hope that we are not morally going to hell in a handbasket, a relentless stream of headlines about moral failures in high office notwithstanding. The men and women cited in this book, as exemplars of conscionable leadership, give us reason for optimism about the character of our future leaders in business and other sectors of society.

These executives operate by a guiding vision of service that takes into account all their primary stakeholders: customers, employees, suppliers and partners in the supply chain, the communities in which they operate, and, of course, their investors. Their companies follow a stakeholder relationship management business model rather than a traditional stockholder-biased business model. At all levels of operation, these companies exude the passion of their leaders for doing good while doing well.

Following Polonius’s advice to his son in Hamlet, these leaders are true to themselves. They evidence keen self-knowledge and project candor and maturity; three essential elements of integrity in their interactions with others. In return, stakeholders in every category place uncommon trust in their companies and products. Beyond this, stakeholders develop a real affection for such companies. They literally love firms of endearment (FoEs).

It is not too much of a stretch to see that as FoEs proliferate[md]and they are doing that[md]the principles of leadership that guide their destinies will be adopted by organizations of every stripe. Indeed, the future well-being of this country could depend more than a little on executive leadership of the caliber and mindset described in this book.

With a title that stands for the empathetic concern of companies that wear their hearts on their sleeves, this book is about the pragmatic role of love in business. However, this is not new ground, as the authors note. Tim Sanders, then chief solutions officer of Yahoo!, lauded the idea of making love a strategic cornerstone of a company’s operations in his 2002 book Love Is the Killer App: How to Win Business and Influence Friends. He wrote, “I don’t think there is anything higher than Love[el]. Love is so expansive. I had such a difficult time coming up with a definition for Love in my book, but the way I define Love is the selfless promotion of the growth of the other.” Three years later, Kevin Roberts, head of one of the world’s largest ad agencies, Saatchi & Saatchi, wrote of brands transcending the mundane foundations of branding to reach a higher level of existence calling them “lovemarks.” He put forth this idea in a book titled Lovemarks: The Future Beyond Brands.

Firms of Endearment is a paean to leaders driven by a strong sense of connectivity to their fellow beings. It celebrates leaders who leverage their humanness by inspiring others to join them in making the world a better place. A few years ago, Timberland CEO Jeffrey Swartz accepted a friend’s invitation to spend a half a day in a teen halfway house. His friend promised him that his life would never be the same. After answering a troubled teen’s question about what he did (“I’m responsible for the global execution of strategy”), he asked the teen what he did. “I work at getting well.” Swartz said later that the teen’s answer trumped his own answer.

Swartz’s friend was right. His life changed that day. He left his office as a hard-driving executive striving to make Timberland the biggest and best in its category and returned as an inspired leader bent on enlisting his entire company in a campaign to “make the world a better place.” That is literally how Jeff Swartz describes his company’s mission today.

Doubtless, some will charge Swartz with shortchanging his stockholders. However, the stock of this footwear and outdoor apparel company has risen more than 700 percent over the past ten years. It has better than doubled in the past three.

The effectiveness of FoE leadership testifies to something most of us have known for a long time but have generally not felt comfortable talking about it in our organizations: Praiseworthy leaders achieve greatness by inspiring love in others for their vision.

Judging by the stories in this book, Yahoo!’s Tom Sanders is absolutely right: Love is the killer app. Love helped turn FoE Southwest Airlines into the most successful airline in history[md]33 years of unbroken profitability. Appropriately, its stock symbol is LUV. Co-founder Herb Kelleher consciously developed a culture of love that ironically encompasses his employees’ unions. FoE Commerce Bank’s founder, Vernon Hill, adapted the “love is the killer app” idea to banking to make Commerce the fastest organically growing bank in America.

The culture of love nurtured by FoE Costco co-founder Jim Sinegal protects shareholders against ill-taken management decisions based on the demands of Wall Street analysts who would have Costco pay employees less, pare back their benefits, and charge customers more. It would be good enough that FoEs simply did well by their nonshareholder stakeholders while modestly rewarding their investors. However, as the authors show, FoEs have generally rewarded their shareholders to an astonishing degree.

In the end, this book is about leadership and the culture that leaders of FoEs develop and nourish. When asked about their biggest competitive advantage, most CEOs of FoEs say it is their corporate culture. Southwest Airlines so much believes this that it has a 93-member Culture Committee. The committee’s job is to ensure continuation of the culture that has made Southwest arguably the most successful airline in history. Committee membership includes employees from every level.

It is hard to imagine the executives we have recently seen led away from their companies in handcuffs spending much time thinking about their corporate cultures. True leaders focus less on their own self-interests than on the interests of the whole. They believe that the full well-being of one depends on the well-being of all. Leaders who focus on their own gains in running a company or other organization are not true leaders. They may be positioned as the head of a global enterprise, a branch of government, a congressional office, a major university, or a local parish, but they are leaders in name only. They command others only by virtue of their positions, not by the content of their character. They are so consumed with self-interest that they are blind to the well-being of others.

All that said, this book makes it easier to imagine that someday not far down the road everyone will demand of leaders in business, corporations, and every other type of organization the kind of impassioned pursuit of a broader purpose found in FoEs. As the authors of this remarkable book observe, two things have happened to make that so. The first is the Internet. As it entered the mainstream of society, it dissolved the information advantage organizations have traditionally had over their constituencies. The Internet has shifted the balance of information power to the masses. This has made it much harder to hide the misdeeds of morally deficient leaders and organizations.

The second event is the aging of the population. For the first time in history, people 40 and older are the adult majority. This is driving deep systemic changes in the moral foundations of culture. Higher levels of psychological maturity mean greater influence on society of what Erik Erikson called “generativity”[md]the disposition of older people to help incoming generations prepare for their time of stewardship of the common good.

Abraham Maslow spoke of people who operate at the higher reaches of maturity as being concerned about matters beyond their own skins. That sums up the disposition of FoEs. With clear-minded certainty about the correctness of their balance between the pursuit of purpose and profits, the leaders of FoEs involve their companies in matters beyond their immediate boundaries[md]generally with felicitous results for shareholders.

Warren Bennis

University Professor; Distinguished Professor of Business Administration

University of Southern California

First Foreword to the Second Edition

I was one of the lucky few who had an opportunity to read the wonderful business book Firms of Endearment while it was still in manuscript form prior to publication. A good friend of mine, Kathy Dragon, was on an airplane several years ago and just happened to be seated next to David Wolfe, one of the co-authors of the book. David was excited about the book, and when he described its content he mentioned that Whole Foods Market was one of the companies they had profiled as a “firm of endearment.” Kathy became excited when she heard this and told David about her close friendship with me, and that I would no doubt enjoy reading the book. David gave her a copy of the manuscript to pass on to me to read.

Such are the small coincidences that can change people’s lives and alter our destinies. To say that I read Firms of Endearment would be a gross understatement[md]I devoured it. Of course I was very happy that Whole Foods was one of the 18 public companies they featured in the book, but that was only the beginning of the impact this book had on me. I was already quite familiar with Stakeholder Theory through my reading of Ed Freeman’s original and brilliant work on the subject, but I was unaware that there were several other companies besides Whole Foods Market that were conducting their businesses in such similarly conscious ways. Up until that point, I had believed that Whole Foods was some kind of unusual odd duck that had created a unique business culture based on fulfilling our higher purposes as a business (besides just making a profit) and consciously creating value for all of our major interdependent stakeholders (customers, employees, suppliers, investors, communities, and the environment). I had thought we were virtually alone in the world and I was overjoyed to discover that there were other well-known businesses that thought and acted in much the same way.

After reading Firms of Endearment, I soon met with David and Raj. We discovered that we shared many ideas and had a commitment to “evangelize” our ideas to the larger world. We began a dialog discussing the ideas outlined in Firms of Endearment[md]ideas that I had been calling “Conscious Capitalism.” We believed that these ideas deserved a much larger audience, and we began to plan our first Conscious Capitalism conference to bring together like-minded people into dialog.

With an initial modest gathering of about 20 people, we launched an initiative to spread the ideas of Conscious Capitalism throughout the world. Many much larger and hugely successful conferences have followed over the past six years. It was at one of these conferences in Boston that I was able to meet the third author of Firms of Endearment, the renowned marketing scholar Jag Sheth. Jag has been a prolific author of dozens of books, including the classic The Theory of Buyer Behavior and Clients for Life. For many years, Jag served as Raj’s mentor, and in that role alone his contribution to the Conscious Capitalism movement has been immense.

Business is by far the greatest value creator in the world. As Raj and I state it in our book Conscious Capitalism (Harvard Business Review Publishing, 2013), “We believe that business is good because it creates value, it is ethical because it is based on voluntary exchange, it is noble because it can elevate our existence, and it is heroic because it lifts people out of poverty and creates prosperity.” Business has such enormous potential to do good in the world. Much of the good is currently being done “unconsciously” simply by creating products and services that people value, providing jobs, and generating profits. However, business can also be done much more consciously, with higher purpose and optimal value creation for all of the major stakeholders while creating cultures that optimize human flourishing.

As people, particularly leaders, become more conscious, we are able to create new types of entrepreneurial enterprises that will help solve our most serious problems and will evolve humanity upward to fulfill our unlimited potential as a species. Firms of Endearment is a very important and ground-breaking book because it points the way that all businesses should aspire to emulate and ultimately transcend. I am grateful to the authors for their landmark contribution to elevating business practice and thereby benefiting humanity.

John Mackey

Co-founder and Co-CEO of Whole Foods Market

Second Foreword to the Second Edition

Second Foreword to the Second Edition

This new edition of Firms of Endearment continues to break important new ground in understanding the power of capitalism to transform our world for the better. In the first edition the authors suggested that firms that pay attention to how they create value for stakeholders might perform better. They gave us an introductory quantitative analysis and a set of rich stories that made the analysis make some sense.

In this new edition they take a giant step forward. They give us a “proof of possibility,” thereby grounding a new story of business in solid economic analysis and practical management thinking. The role of passion and purpose is not well understood in a world where the dominant story of business that we read everyday suggests that only money and profits count.

Furthermore, this dominant story suggests that businesspeople are greedy and self-interested. We see this played out everyday in the press, in government responses to crises, and sometimes we see executives themselves making the same attributions. It’s time to stop this nonsense, and the authors give us a roadmap.

Every business always has and always will create value for customers, employees, communities, suppliers, and the financiers who put up the investment. Firms of endearment are those companies that realize this principle of stakeholder value creation and orient themselves around it. These are the companies we love to do business with. They are the brands we recommend to our friends, and if we are smart, they are the investments we have in our portfolios, 401(k) plans, and so on.

None of what this book says should be surprising. What is surprising is the resistance that can be encountered. Many narrow-minded economists, as well as many critics of business, just “know” that business is really about the money. They then make the logical error of inferring that the purpose of business is to make as much money as possible.

That’s like saying that because we need red blood cells to live, the purpose of life is to make red blood cells. Our great companies, including the ones in this book, but in the past as well, are fueled by passion and by a sense of purpose. Great business leaders channel their employees’ desires to be a part of something bigger than themselves and to be a part of making the world a better place for their children into the overall purpose of their business. Profit is an outcome. And, of course, there are no guarantees here. Sometimes companies do their best around a purpose and indeed fail, or they fail to keep that purpose in front of them, or conditions simply change.

The twenty-first century requires a new way of thinking about business. Thankfully that story is beginning to emerge with books like Firms of Endearment. It will repay close study, seeing how your company is both like and unlike the examples in the book. And, hopefully it will cause you to ask questions about your own purpose, both in terms of your company and your individual situations.

This is not the end of the new story of business, but it is a good beginning. Hopefully it will inspire others to “critique by creating something better.” I urge you to see it not as the definitive word on how to run a business, but as a proof of possibility that creating value for stakeholders with purpose and passion is an idea that works and whose time has come. It offers hope that we can be the generation that makes business better and leaves a better world for our children.

R. Edward Freeman

University Professor; Elis and Signe Olsson Professor of Business Administration

The Darden School, University of Virginia

Meet the

Firms of Endearment

All logos are copyright of the companies

All logos are copyright of the companies

All logos are copyright of the companies

Performance of

Firms of Endearment

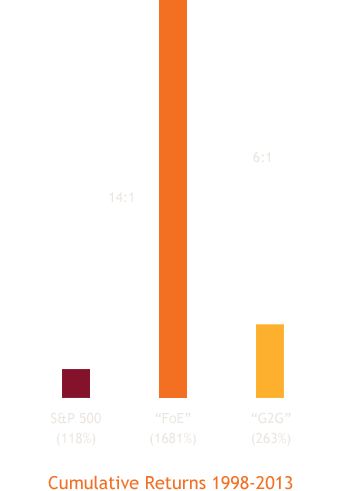

The firms of endearment featured in this book have out performed the S&P 500 by 14 times and Good to Great Companies by 6 times over a period of 15 years.

| Cumulative Performance | 15 Years | 10 Years | 5 Years | 3 Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| US FoEs | 1681% | 410% | 151% | 83% |

| International FoEs | 1180% | 512% | 154% | 47% |

| Good to Great Companies | 263% | 176% | 158% | 222% |

| S&P 500 | 118% | 107% | 61% | 57% |

Recommend a

Firm of Endearment

Your Details

Write in to

The Authors

RAJ SISODIA

email: rsisodia@babson.edu

website: www.rajsisodia.com

JAG SHETH

email: jag@jagsheth.com

website: www.jagsheth.com